For the early Kashmiri Śaivas, consciousness was architectural, the blueprint of being. They sought to understand how awareness could give rise to the structure of our reality. How might their vision reshape the questions we ask about mind and reality today?

The Two Properties of Consciousness :

Revealing Aspect: Consciousness acts like light, revealing things and allowing them to be perceived, just as a light source illumines an object in a dark room and makes it known. (Prakāśa /Śiva)

Self-Reflecting Aspect: Just as light needs no second light source to be seen, it is already visible by its own radiance. Consciousness is self-luminous. We do not need a second “perception” or “witness” to confirm that we are perceiving. The very act of perceiving already carries within it the awareness of perception. (Vimarśa /Śakti)

The Two Properties of Consciousness Cannot Be Separated from Each Other

When looking at an object, both aspects of consciousness operate simultaneously — the object is known to us (revealing aspect) and the knowing of it becomes evident to us (self-reflecting aspect).

Though they are inseparable in Śaiva philosophy, modern machine learning offers an instructive contrast. For it simulates the revealing function but not the self-reflecting aspect. That very split differentiates it from conscious entities.

There Is Only One Absolute Consciousness, but Why?

To claim there are many distinct conscious sources — yours, mine, and everyone else’s — we must be aware of them all, as members of a set (a set of consciousness). But the awareness of that set is itself a unifying consciousness. Every perception of multiplicity already occurs within one field of awareness. It is as if we draw lines across open space to divide it into regions but those regions remain contained within space itself. The lines never truly break the space that holds them.

The one light of consciousness illuminates every object, and every object is known by the same light. Hence, every object shares a common nature, the fact that it is revealed by the same awareness, and they cannot exist outside of that unity. Not only are things known by the same consciousness, but they also appear within consciousness, and nothing can appear outside it. What we perceive are reflections within the mirror of consciousness, but not the objects themselves.

Some non-dual schools phrase the relation between consciousness and appearance differently. They describe appearances as consciousness rather than in consciousness, rejecting any further distinctions or duality.

Consciousness as the Absolute Reality in the Śaiva Perspective

If the Absolute is that beyond which nothing can occur or be conceived of, then consciousness itself meets this definition (not to be confused with panpsychism). The very idea of anything appearing outside consciousness also arises in consciousness. Therefore, consciousness cannot be contained in anything else, and it is that very condition, the Absolute itself.

It is not a property within the universe, like space or time, but the framework within which the universe and its properties, such as space, time, and causality, arise and become conceivable. This isn’t a chronological claim but a logical relation.

The Pulse of Consciousness

Imagine being aware of a photograph. Now imagine being aware of a video. The fact that we can experience continuous change — movement, sound, time, motion, and yet hold it all together as a coherent stream implies that what appears within consciousness is dynamic. The video analogy illustrates how appearances within consciousness are dynamic. We don’t experience gaps in consciousness, but even within that continuous field, there’s variation: the rise and fall of our thoughts, shifting attention, and moving perceptions. But if consciousness itself were not dynamic, how could we ever know? We’d be characters within a video game, unaware of the game being exited or saved at a checkpoint. Regardless, the appearances within consciousness are dynamic. If the appearances were truly static, like a frozen light, it could illuminate things but not experience anything. This dynamism within consciousness is what the Śaivites call the “pulse” (Spanda). It is not motion in space or time but the intrinsic reflexivity of awareness.

The Three Inseparable Moments of the Pulse

The pulse of consciousness unfolds in three inseparable moments:

Expansion: Awareness moves outward, and something comes into focus or arises in experience.

Stability: Sustenance of the object long enough for it to be known.

Contraction: Awareness shifts towards itself.

When consciousness expands into multiplicity, it’s not “forgetting itself”. It’s contracting its unity to expand into many forms. When consciousness withdraws from multiplicity, it’s not “shutting down”. It’s expanding inward into its own unity by contracting its multiplicity. These are not successive stages in time but codependent movements of consciousness.

The Three Capacities of Consciousness

Openness to something new appearing within itself (Icchā Śakti). Example — Potential for a thought to arise.

Recognition of the appearance in itself (Jñāna Śakti). Example — Recognizing the thought and what it is.

Realization that the appearance is actual rather than a mere potential (Kriyā Śakti). Example — The thought has become an actual occurrence within awareness.

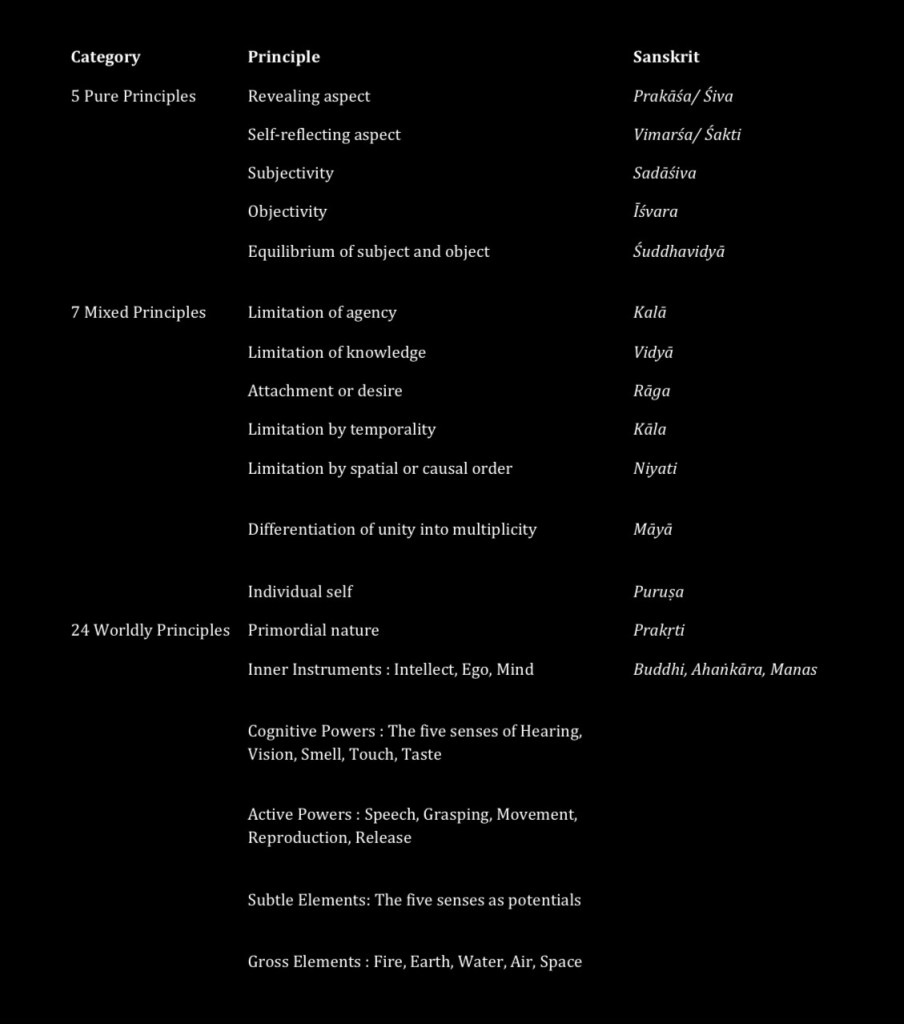

These are not sequential but coexistent potencies of consciousness. From these three capacities, awareness unfolds into degrees of manifestation – known as the 36 tattvas – which represent the differentiation of awareness into multiplicity.

This unfolding into multiplicity takes shape through progressive self-limitations. The higher levels of manifestation reveal consciousness in its more expansive, self-aware modes, while the lower levels show its gradual self-contraction – when it appears as forms of mind, sense, and matter, seeming to become embodied as sensory awareness. It is said that a deeply realized mind can experience many of these states directly, not as altered psychological states of mind but as subtle shifts in the self-recognition of awareness. Ultimately, awareness appears as the entire embodied world, what they call the divine body.

Contemporary Implications

Extending this idea beyond this framework raises a familiar question: if the mind is an appearance within consciousness rather than an independent source of consciousness, do we truly have free will? But this question lies outside of our inquiry, for consciousness does not equate agency. Whether the mind possesses its own consciousness or merely reflects the light of a larger consciousness has little bearing on whether the mind has free will. Hence, the debate between free will and determinism belongs not to consciousness or the mechanical structure of the mind but to the independence from a greater causal chain because even a self-aware machine could be entirely deterministic.

The goal of their philosophy was to understand the nature of the Absolute as a unity that reveals itself through multiplicity. As the philosopher Abhinavagupta explained:

If oneness and duality truly opposed each other, they would belong to two separate realities, which would contradict the very notion of oneness.

Further Reading :

Dyczkowski, M. S. G. (1987). The doctrine of vibration: An Analysis of the Doctrines and Practices Associated with Kashmir Shaivism. SUNY Press.

Utpaladeva. (2013). The Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā of Utpaladeva: Critical edition and annotated translation (R. Torella, Trans. & Ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Müller-Ortega, P. E. (1989). The triadic heart of Śiva: Kaula tantricism of Abhinavagupta in the non-dual Śaivism of Kashmir. State University of New York Press.

Note: The ideas presented here are not my personal metaphysical claims but an overview of the broader non-dual Śaiva tradition of Kashmir. I do not represent any single school or lineage within that tradition. This is intended to introduce how consciousness has been understood as an architectural mode of reality to readers unfamiliar with this philosophy.

Leave a comment